Two photographers, David Watson and Park, HongChun look at familiar places with new eyes, one with an impressionistic approach to colour, the other with a time-exposed meditation on colour.

The thermometer soars to thirty seven degrees. ‘I’m dreaming of a white Christmas’; in city malls and shopping precincts, loudspeakers feature Bing Crosby. But nearby, at the Palm House of Sydney’s Botanic Gardens, the mid summer light bounces from glass surface to glass surface, and the resulting impression of dazzling white owes very little to the snow that Bing, stuck in a recorded loop, dreams of in some bygone era, a hemisphere away.

The Palm House, built in the Victorian era, was designed to protect the plants of another climate from the harsh Antipodean sun. It’s now a site for exhibitions of the visual arts and last December it housed David Watson’s photographic series New south wonderland. Watson began taking these photographs when he returned to Australia in the late nineteen eighties. After living in England for many years, he saw formerly familiar Australian landscapes with new eyes; in contrast to the muted light of the northern skies he had become accustomed to, the Australian suburbs with their fibro houses and red roves beneath hot blue skies suddenly seemed as bright as those of Florida. On first impression, the photographs are a blur of light and colour, moments of exposure to everyday places; from a block of flats at night to patterns of sunlight on bark; from glimpses of a suburban bungalow to a pathway through a bush clearing. Watson is particularly interested in the possibilities of images that are deliberately ‘out of focus’ places evoked not in sharp black and white, but through patterns of colour, light and shadow.

Many of the photographs in New south wonderland rely on controlled palettes of colour: the vivid red flash of a car against the subdued shades of asphalt, a strip of roadside buildings and signs that look as if a Walker Evans scene has come to life in a different era. The muted brown of a bush track unfurls against a green field and then, in the distance, we can discern the deep hues of grass and trees. In a neighbourhood garden, the shadow of a tree falls against rich brown earth; in the immediate background we can just make out a row of flowering shrubs against the white walls of the house. Another image shows a field of pale green dotted with darker green and mauve-purple, a narrow band of sky on the horizon. The simplest colour names – red, blue, green, white, grey, gold – seem to suit these impressionistic fields and patterns of colour. Skies are rarely blue, they’re more often blown out to soft grey or white. This helps create the sense of an endless summer, moving around looking closely at a familiar world made unfamiliar through the glare of light.

Places, rather than people, are paramount. When people are present – for example, the movement of a woman in gold bathers as she makes her way through a blue-green sea –they are simply one element in the frame, part of a larger design. It’s places that occupy centre frame. But they’re nearly always partial views. These photographs rarely allow us to see far into the distance, to consider the elements in the environments depicted in anything resembling a ‘normal’ perspective. They’re close-up and there’s a sense of intimacy with the places and landscapes they depict. Many of Watson’s photographs work with recognizable shapes and forms: we’re presented with the outlines of houses or trees. There’s just enough detail for memory and imagination to begin their work.

Watson claims influences as varied as Robert Frank’s black and white photographs infused with the blurred light of the early tele-visual age, Nancy Rexroth’s experiments with toy cameras to ‘not define’ her native Ohio and Melbourne photographer Graeme Hare’s close-ups of gardens.

A preoccupation with the evocative powers of light runs through New south wonderland. Many of the photographs feature light in motion. In one arresting image, a branch overhangs a house with a bay window and a front gate seems to be moving on its hinges. Streaks of light like strips of white neon travel up the front path. The resulting effect is of a relatively ordered house and yard, depicted in shades of pink, gold and green, suddenly vibrating with light and warmth. The dynamic element, the streaks of light, force us to re-consider and resolve a scene that’s not what it seems at first sight. For me, a photograph of a block of flats, lit at night, almost summons forth sea air. The image conjures up Bondi when I first arrived from Adelaide about fifteen years ago. With no job and no money, I would walk around the neighbourhood at night, gazing at blocks of those lit windows, wondering whose lives and stories they contained.

Lights, gates and paths are imbued with an almost spiritual significance in Watson’s photographs. His New south wonderland includes both the red-painted concrete front paths of inner city buildings and tracks cleared through the bush. Many of the images are tranquil. But not all. There’s the shadowy outline of a dog, poised in indecision at a suburban crossroad. Looking down the street, we see brick villas, tiled roofs and sunlit hedges on one side, deep shadows on the other. Which side of the street will be chosen, sunlight or shadow? The photograph depicts a moment of reckoning or decision making.

One weekend, I watch visitors make their way through the exhibition and later, read some of their comments. A sense of wonder and delight dominate the responses. Perhaps because Watson’s images so deftly evoke the meanderings and pathways we all create through our daily lives, making patterns of meaning that only become significant after considerable time has elapsed. But, for all their evoking of place, memory and imagination, there is an energy about the photographs that make up New south wonderland, they invite an active visual response to our everyday worlds. They’re images that remind you of the pleasures and rewards of paying more attention to the seemingly ordinary, of seeking the disparate in the ordered and the composed amidst the chaos of the immediate.

|

|

Korean photographer Park, HongChun’s photographs of Australian seashores invite reflection through different means. Park’s photographs were shown with the work of other contemporary Korean visual artists in an exhibition The slowness of time held in both Seoul and Sydney in 1998 and 1999. Perhaps Park’s photographs come to mind after viewing New south wonderland because colour is so important, too, in Park’s classically composed, intensely contemplative photographs. I first saw these photographs in a group exhibition at the Hoam Art Hall Gallery in Seoul, wandering the city as snowflakes fell in mid winter. Fortunately there was no Bing Crosby soundtrack. In a metropolis filled with restless motion, neon, laser displays, and surfaces seemingly capable of shifting from building to video screen in a micro-second, opening the door to The slowness of time was like opening a door to another world or, at least, a less visible world.

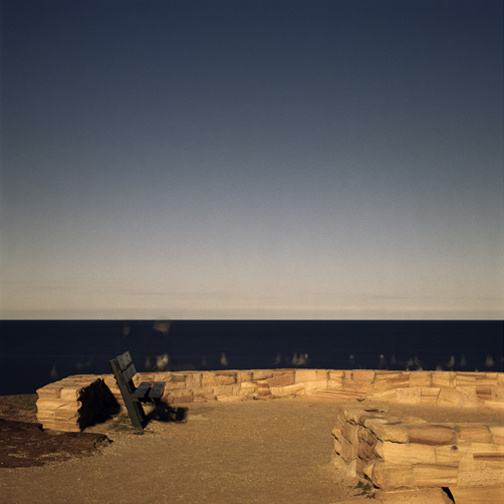

At first Trace subject matter seems deceptively simple: a series of photographs of wooden benches against expanses of ocean and sky. (Park took these photographs at Melbourne and Sydney beaches on a visit to Australia.) They’re light years away from the usual postcard images of Australian beaches with their sun and surf and bronzed bodies. The photographs almost invite you to take your own place at one of those seaside benches and look, both outward and inward. Raymond Carver describes doing something like that in his poem Sweet light; ‘I pulled up a chair. Sat for hours in front of the sea. Listened to the buoy and learned to tell the difference between a bell, and the sound of a bell’. Trace’s images are compelling, their colours soft and muted with a palette skewed toward magenta. Looking closely, there’s an impression of endless gradations of individual colours, chromatic pools in which you can almost lose yourself. Park’s work is not only beautifully eloquent but technically assured.

The shapes and lines of benches and picnic tables give form to what would otherwise be layers of sky, sea and grass. All photographs are about time but these photographs, with their carefully composed fields of washed out blues, mauve, and pink, their long exposures and undertones of melancholy, particularly invite a meditation on the nature of time. Park creates the illusion that time is something that, at least momentarily, we are in control of, as time seems to flow through the frames, even and measured. Here it stretches backwards and forwards. It is not calculated according to the scale described in James Glick’s Faster, a contemporary world obsessed with measuring time to the extent that even a twenty dollar watch can measure time to one part in a million accuracy.

And since there is nothing extraneous or incidental in these photographs, each compositional element assumes considerable weight. A streak of cloud across the sky, a windswept stand of saltbush, light hitting the wooden railing of a jetty; they all demand our attention. Amidst the endless expanses of magenta-tinged blue, single clouds and bushes or the earthy tones of stone and wood create a sense of the scale of humans. They ground us and return us to the present. Park has developed his distinctive approach to time and colour over a series of photographic subjects over the last ten or more years, poetically re-imagining not only seascapes but amusement parks and cities around the world. In the world filtered through his sensibilities, Bondi, Tokyo or Disneyland are not teeming with people but deserted, eerie landscapes haunted rather than inhabited by humans. These are deeply resonant, accomplished works.

Both photographers’ images look at Australia with new eyes, drawing on subjective images of the past to unsettle the familiar. But who can say where memory ends and imagining begins? Where the process of composing and re-composing or focusing and re-focusing the past ends? And imagining the future begins?

New south wonderland, photographs by David Watson, was at the Palm House, Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, December, 2000; Park, HongChun: His work and his world is a monograph published by Gallery Samtuh, Seoul, Korea.

Kathryn Milard's essay was published in the Art Monthly Australia, Apr. 2001.

Kathryn Millard is a screenwriter and director. She is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Media and Communications Studies at Macquarie University.

|